- K

- Jul 21, 2020

- 5 min read

Updated: Jan 18, 2024

TLDR version

Discount rate is investor-driven. Every investor has different expectations on returns, which implies the discount rate is subject to bias.

The CAPM model for deriving cost of equity is historical-looking and based on the perspective of a fully diversified investor. As such its relevance to the future and the target company must be taken with a pinch of salt.

Don't neglect the importance of analyzing future cash flows when using the income approach. Discount rate isn't everything.

Most analysts and associates that I know tend to get very caught up in the math and precision of calculating the discount rate when it comes to doing discounted cash flow valuation.

I have a healthy respect for the work and research that has gone into developing the industry standard for the discount rate or WACC (weighted average cost of capital) - which is extensively used by most people in the world of finance. However, in reality, I don't see why any investor should dwell too much on the accuracy and precision of the discount rate - especially when it comes to valuing deals in emerging markets.

Warren Buffet summarizes this aptly:

"Volatility is not a measure of risk. And the problem is that the people who have written and taught about volatility -- or, I mean, taught about risk -- do not know how to measure risk. And the nice about beta, is that it's nice and mathematical, and wrong in terms of measuring risk. It's a measure of volatility, but past volatility does not determine the risk of investing."

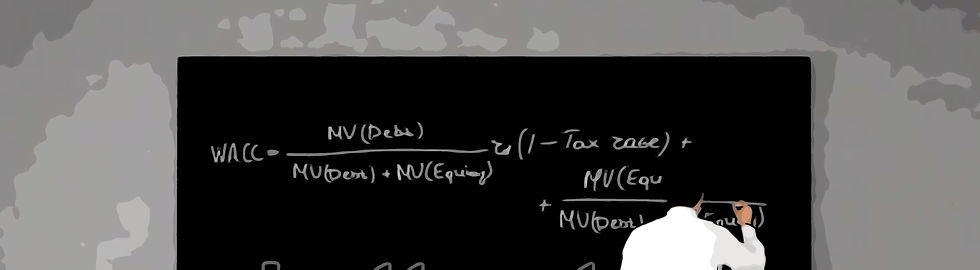

WACC as a discount rate

It reflects returns expected by all the stakeholders in the business. Debt holders get their returns in the form of interest and principal, while equity holders (shareholders) get their returns through dividends or whenever they sell their shares in the company.

The model behind quantifying risk and returns are incredibly correlated with share price movements as public markets provide the most visible and transparent form of valuation.

The theory is that: The share price of a company generally moves in tandem with the overall market. The riskier the company, the more the prices deviate from the benchmark indices. Risk in this case is driven by the industry dynamics as well as the amount of debt the company holds. More debt means more risk and therefore more share price deviation. The beta in the capital asset pricing model tries to quantify this.

There are a number of factors that go into the calculation of the beta:

Choice of company and market benchmark to compute the data points

Relevance of the company being selected for the comparison

Sample duration (1 year or 5 years?)

R-squared of the dataset

Assuming that you can accurately triangulate the above datasets, the outcome of the analysis is still inherently based entirely on historical data, which we already know, cannot be used as an accurate basis for predicting the future.

Comparison is the name of the game in valuation.

The industry-standard for deriving the discount rate involves comparisons with market benchmarks such as government bond rates, indices and comparable companies. In layman terms, what this means is:

"If I invest in a similar bond or financial instrument and get a X% return, why should I invest in you for the same?"

The discount rate for companies are priced at a premium because they are perceived to have higher risk than a certain market benchmark. In most cases, this is pre-defined as the expected returns from putting capital to work in a mature and diversified financial market with the following attributes:

Little or no history of defaults on sovereign bonds;

Triple-A rated by credit agencies

A stable political governance framework (a possibly contentious assumption under today's incumbent president) and;

The existence of a highly liquid and transparent equity capital market.

The price movements in the markets are also dominated by different investor profiles: Hong Kong has been traditionally seen as the capital markets gateway for companies with significant exposure to Greater China, while Singapore is noted for its position as a "safe haven" for wealthy asset managers hungry for yields, making the listing of real estate investment trusts ('REITS') hugely popular with the its exchange.

Likewise, the companies listed on the ASX, TYO and KRX are also largely shaped by the their home country's trade and industry dynamics. The resulting beta calculated from each of these markets will be to a certain extent, driven by the largest companies listed on the respective exchanges.

An appropriate benchmark for a mature market?

Most firms continue to use the US market as the benchmark. Research states that this is approximately 5.23%. Is a "mature market" in Asia - one which has stable financial and geopolitical regime - be compared and likened to the US? Can we equitably also say that the returns for investing in a mature Asian market are also 5.23%?

Take Hong Kong for example: It is a key and unarguably mature financial center in Asia, constantly perceived as a gateway to China. In the last couple of years, the city has also been caught in the epicentre of social unrests stemming largely from geopolitical factors. How does one marry the two to derive the equity risk premium in a market such as HK? Can we appropriately coin HK as a stable equity market? For a foreign business looking to enter Asia/China, would you use the mature market risk premium as the basis for your budgeting calculations?

Risk is ultimately a game of probability and uncertainty, and not volatility.

Uncertainties are driven by external factors such as geopolitical events; while internal factors refer to the company's business plan which drives the visibility of future cash flows. In a period of significant uncertainties, the application of the discount rate becomes less relevant.

Additionally, every investor out there has different appetite for risk, and these are shaped by their degree of understanding and comfort levels in the business and the market it operates in.

Every investor who receives a pitchbook of a company profile knows that the valuation number in the deck is whatever the banker wants to portray in order to win the mandate. The discount rate is irrelevant. A smart investor knows that validating the DCF valuation presented by the banker takes more than just a meeting but a deep dive into the operating drivers and free cash flows.

Rather than spend time dissecting and defending the WACC, you are better off analyzing the company's underlying fundamentals.

Most business meetings involving pricing comes down mostly to market multiples: P/E ratios, EBITDA multiples, EV/Sales. These ratios are intuitive, easily applied and comparable across geographies and businesses. It may not be rocket-science accurate but at least everyone sitting in the boardroom has sufficient understanding of the literature to make a decision.

In some cases, valuation can also be totally irrational. Investors will acquire a business 'at all costs' to gain a foothold into the lucrative markets of Asia regardless of what the discount rate shows. It makes the WACC calculation sound like a bunch of pig latin but that's the reality of asset pricing, especially in emerging markets.

There are still many merits to understanding a company's cost of capital (read also my article on DCF and LBO). Cost of capital is important in capital budgeting and knowing the limits of your borrowing capacity.

Unless the most important stakeholder in the room (which most of the time happens to be your client) asks for a scientific breakdown of the WACC, you'll find that most of the time, the discussions around valuation are going to be on cash flows and market multiples.